Categories, tags, and the broader idea of taxonomies#

Websites that use categories and tags#

Categories and tags are most common on content-management-driven websites, where content is published continuously and needs to be organized, discovered, and reused over time. For example:

- Blogs and personal sites

- Media and publishing sites

- Knowledge bases and documentation portals

- Research libraries

- Corporate content hubs

In all of these, content is not just pages, it’s a growing body of material that benefits from structure beyond simple navigation menus.

From categories and tags to taxonomies#

Categories and tags are not special in themselves. They are simply two well-known examples of a more general concept called a taxonomy.

What is a taxonomy?#

A taxonomy is:

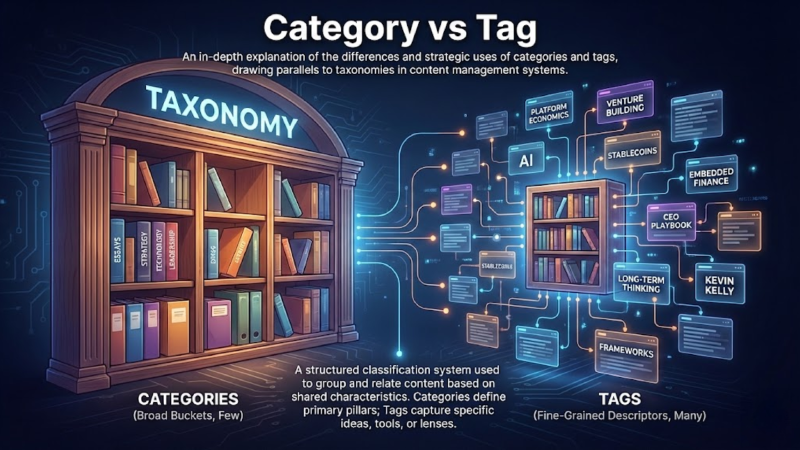

A structured classification system used to group and relate content based on shared characteristics.

In practical terms, a taxonomy allows you to answer questions like:

- What kind of content is this?

- What themes does it relate to?

- How does it connect to other content?

- How should users browse or filter it?

Taxonomies come from fields like biology, library science, and information architecture, but they are now a core concept in modern web systems.

Why categories and tags became defaults#

Historically:

- Categories emerged as top-level groupings (few, broad, stable)

- Tags emerged as descriptive labels (many, flexible, granular)

They proved so useful that most content management system (CMS) platforms adopted them as defaults.

But conceptually:

- Categories = one type of taxonomy

- Tags = another type of taxonomy

They differ mainly in intent and governance, not in underlying mechanics.

Modern frameworks and “custom taxonomies”#

Modern content frameworks (static and dynamic) generalize this idea.

Instead of hard-coding only “categories” and “tags”, they allow you to define:

- Any number of custom taxonomies

- With custom names, rules, and behaviors

- Applied selectively to different content types

Examples of additional taxonomies might include:

series(multi-part content)topics(curated themes)industriesframeworksuse-casesrolesorperspectives

Each taxonomy:

- Groups content

- Generates its own listing views

- Supports navigation, filtering, and discovery

In other words, categories and tags are conventions, not limitations.

The key idea to internalize#

Categories and tags are just named taxonomies with historical defaults. What matters is not the labels—but the classification intent behind them.

Modern frameworks give you the tools to define:

- How content should be grouped

- How users should explore it

- How ideas connect over time

The discipline lies not in adding taxonomies, but in knowing when a new lens genuinely improves understanding.

That’s the difference between a blog archive and a durable knowledge system.

Back to the diference between categories and tags#

When using tools like Wordpress or Hugo for a websites, tags and categories are both taxonomies serving different strategic purposes.

The short version#

Categories = broad buckets

- High-level themes

- Few in number

- Usually 1 (maybe 2) per post

Tags = fine-grained descriptors

- Specific topics, ideas, tools

- Many in number

- Often 5–10+ per post

Think of it like this:

Categories answer: “What kind of content is this?” Tags answer: “What exactly is this about?”

Categories: your site’s macro-structure#

Categories define the primary pillars of your thinking.

For a personal brand site like mine, good categories might be:

EssaysFintechStrategyLeadershipTechnologyEnergy Transition

Rules of thumb

Keep categories stable over years

If you add one every month, you’re doing it wrong

Categories often map to:

- Nav items

- Top-level content sections

- “What I write about” framing

Example post front matter

categories:

- Strategy

Tags: your semantic graph#

Tags capture specific ideas, tools, or lenses that cut across categories.

Examples from my own site:

embedded-financeplatform-economicsstablecoinsventure-buildingaiceo-playbooklong-term-thinking

Tags are powerful because:

- They enable cross-pollination

- They create a knowledge graph of your thinking

- They age well even as categories stay fixed

Example front matter

tags:

- platform-economics

- venture-building

- long-term-thinking

- kevin-kelly

A practical mental model (very useful)#

Use this decision test:

- If someone asks “What kind of writer are you?” → Category

- If someone asks “What ideas do you explore?” → Tags

Or:

- Categories = bookshelf labels

- Tags = index entries

SEO & discoverability implications#

Categories

- Stronger internal linking

- Clear topical authority

- Useful for cornerstone / evergreen pages

Tags

- Long-tail SEO

- Better content resurfacing

- Encourages deeper session depth (“related posts”)

For personal sites, tags usually do more work than categories.

Common mistakes to avoid#

- ❌ Using tags and categories interchangeably

- ❌ Having 30+ categories

- ❌ One-off categories used once

- ❌ Putting people’s names as categories

- ❌ Treating categories as chronological (that’s what dates are for)

Recommended setup for a personal site#

Categories

- 5–8 max

- Strategic, durable, opinionated

Tags

- Flexible

- Reused intentionally

- Reflect how you think, not generic blog taxonomies

Example (applied)#

For my Kevin Kelly / platform economics post:

categories:

- Strategy

tags:

- platform-economics

- business-models

- ecosystems

- kevin-kelly

- long-term-thinking

That tells both humans and search engines:

- This is strategic thinking

- About platforms, ecosystems, and long-term dynamics