Let’s take a deep dive into the DNA of high-performance organizations. We’re talking about something that’s often shoved into a dusty HR handbook: company values. But trust me, in today’s cut-throat, rapid-growth, tech-driven world, values are not a soft skill or an afterthought. They are a mission-critical instrument for alignment and, frankly, operational efficiency.

Some big questions to tackle: Where do these values actually come from? Is it some kumbaya, bottom-up discovery session, or a rigorous, top-down mandate? And here’s the real gut check: How do you know you’ve nailed the right ones?

Now, let’s talk durability. Values should be durable, but absolutely not immortal. They need to survive annual budget cycles, sure, but the moment your strategy defines a major pivot or an existential transformation, those values need to be reviewed and likely go straight to the chopping block. You need to audit them to make sure they’re not the anchor dragging you down.

I’ve spent time integrating frameworks from management gurus with real-world examples. Think the legendary, low-cost culture of Southwest Airlines, or the customer obsession machine that is Amazon. And what I’ve found is a roadmap for the founder or the leader, on how to encode your intent directly into the organizational DNA. The core idea is this: values aren’t just polite behavioral descriptors. They are a deep, practical tool used to solve the specific, diagnostic challenges of your firm.

Beyond the Wall Plaque: Values as Decision Heuristics#

Walk into a company lobby (almost any company lobby!) and what do you see plastered on the wall? “Integrity.” “Excellence.” “Teamwork.” “Respect.” Now, they sound nice, right? Feel-good words. But let’s be brutally honest: they’re utterly meaningless. They’re what happens when corporations have a crisis of distinctiveness, a severe case of the blands. They’re trying so hard to appeal to everyone: every potential hire, every customer, that they end up standing for absolutely nothing. And when this happens, you’re not looking at a small marketing slip-up. You are witnessing a catastrophic failure of strategic leadership.

Because true corporate values? They are not just nice little posters for the water cooler. They’re the DNA for every single decision made when the CEO isn’t in the room. They’re the playbook that tells your team, “When you have to choose between Option A and Option B, for example, speed versus accuracy, or individual autonomy versus group coordination: this is the trade-off we make.” They are heuristic shortcuts that guide complex decision-making, not just aspirations for a pleasant workplace.

Top-Down Value Alignment#

Existential strategy and values are inextricably linked. Just as strategy requires making hard choices about “where to play” and “how to win,” value setting requires making hard choices about “who we are” and, perhaps more importantly, “who we are not.” Here’s my hot take which may ruffle some feathers: this idea that you can just crowdsource your company values from a massive employee survey? It’s a complete and total leadership cop-out. It’s a dereliction of duty. If the management team is the one on the hook, accountable to the shareholders for the firm’s ultimate performance, then they absolutely must have the authority to dictate the cultural operating parameters required to achieve that performance.

It’s a top-down game, and it mirrors how we set strategy. Roger Martin, one of my favorite thinkers on the topic, says strategy is a set of definitive choices made by leadership, not some lukewarm synthesis of data that just bubbled up from staff. The leadership team owns the destination, so it follows that they have to own the vehicle (the culture) that’s going to get them there.

And this necessity gets cranked up to eleven when you’re facing transformational change. Let’s be real: Innovation is messy. It’s risky. In the short term, it is wildly inefficient. If your organization’s DNA, its tacit unspoken values, puts “efficiency” and “error prevention” above everything else, which, let’s be honest, is typical of most established legacy institutions, then innovation won’t just struggle; it will be suffocated. It will die before it ever yields a single return.

Therefore, the leader’s role is to impose a value system that creates a protective embrace around the messy process of creation, effectively overriding the organization’s natural antibodies against change.

The Economic Necessity of Alignment#

Let’s dive into a concept that sounds dry, but it is anything but: The economics of setting values. I’m talking about why the CEO and the Board must set the company’s operating values from the top down. This is classic Principal-Agent theory. The Board and the CEO are the Principals. They’re the fiduciaries for the shareholders. Their job is to set the strategy: the big plays for profit. Is it winning on price? Is it cutting-edge efficiency? Is it conquering new markets?

Now, the Agents are the entire employee base. They have to execute this strategy. But here’s where the rubber meets the road: If the employees’ values, their internal operating code, are fundamentally misaligned with the Principals’ strategy, you get friction. It’s like trying to run an electric car on gasoline. It just doesn’t work.

Think about this scenario: You’re a financial institution. Your strategy is all about rapid digital transformation, to be the disruptor. But what do your people value? Likely stability, consensus, maybe even a little risk aversion that they politely call “prudence.” What happens? The strategy dies in execution. Decision cycles slow to a crawl. New initiatives get quietly resisted, maybe even subverted. That friction? That’s an economic cost. It’s why imposing values isn’t just a feel-good HR exercise; it’s an act of economic efficiency. It makes sure the human engine is psychographically suited to the mission.

The cost of that misalignment? It’s not linear; it’s exponential. In today’s fast-moving market, if a team hesitates on a strategic pivot because they secretly value “consistency” over “agility,” they don’t just lose a little ground, they miss the market window entirely. If your organization celebrates “process” over “progress,” all that disruptive energy you hired for? It’s not turning into forward motion; it’s just being burned off as wasted heat.

The Failure of Bottom-Up “Discovery”#

A common error is the “bottom-up” values exercise. You survey everyone, you ask them what they value, and then you plaster “Respect” and “Integrity” on the lobby wall. Sounds democratic, right? Sounds inclusive?

Well, let me tell you, that process has two absolutely fatal flaws.

First: It’s a total Regression to the Mean. Think about it. When you survey a large group of people: a hundred, a thousand, you’re going to converge on the stuff nobody objects to. You’re going to get “hygiene” factors: safety, fairness, politeness. Everyone values “Respect.” Everyone values “Integrity.” But as a strategic differentiator? As something that makes your company different and better? They are utterly useless. It’s the business equivalent of saying your competitive advantage is “breathing air.”

And the Second Fatal Flaw? It’s the backwards causality. By letting the current employee base define the values, you’re making a massive assumption: that your current workforce is perfectly aligned with where the firm needs to go. If your company is trying to pivot from a steady, predictable operation to, say, a disruptive tech innovator, guess what? The current staff may hold values (like stability and risk-aversion) that are completely antithetical to the required future state.

The cold, hard truth? Values must be set and reviewed by the leadership. Period. Why? Because leadership is accountable for the outcome. And if you’re accountable for the outcome, you must define the inputs, including the cultural inputs.

If the staff’s values differ from the leadership’s values, the solution is not to water down the company values to match the staff. It is to change the staff to match the values. It’s a harsh reality, but it is the necessary logic of accountability. Leadership defines the cultural north star.

The Transformation Context#

There is a difference between operating strategy (which changes frequently) and existential strategy (which changes rarely).

I alluded to the transformation, or disruption, case above. This is the specific moment when a leader must revisit core values and “architect” a new soul for the company to survive a major pivot. The general rule of values being perennial (“preserve the core”) applies to companies in a steady state.

Values are a tool to help solve a specific business “diagnosis”. Values should only change when that fundamental diagnosis changes, not when tactical plans change.

- Scenario A: Tactical Change (No Value Change)

- Strategy Shift: The company moves from selling software licenses to selling subscriptions (SaaS).

- Diagnosis: We are still fighting for market share in a competitive tech landscape.

- Values: “Agility” and “Customer Obsession” remain valid. Changing them would cause confusion.

- Scenario B: Existential Pivot (Mandatory Value Change)

- Strategy Shift: A legacy bank decides to become a digital-first fintech builder.

- Diagnosis Change: The old diagnosis was “Protect the Assets” (Stability). The new diagnosis is “Disrupt the Market” (Speed).

- Reconciliation: The old value of “Prudence” is now an “antibody” that will kill the new strategy. Therefore, the value must change to “Bias for Action” to allow the strategy to survive.

The “Transformation” Exception#

An exception to the durability of values occurs when the organization is in a state of crisis or rapid evolution.

- Microsoft Example: When Satya Nadella took over, the strategy shifted to “Cloud First.” He recognized the existing culture of “internal competition” (which served the old Windows monopoly strategy) would destroy the new strategy. He explicitly changed the core values to “Growth Mindset” and “One Microsoft” to enable the pivot. Similar to the One Ford value advanced by Alan Mulally when he took over an ailing Ford Motor Corporation.

- Uber Example: When Dara Khosrowshahi replaced Travis Kalanick, the strategy shifted from “Growth at all costs” to “Sustainable public company.” He had to delete core values like “Toe-stepping” because they actively sabotaged the new objective.

Differentiating “Core” from “Accidental”#

The “general rule” that values shouldn’t change refers to deep, timeless principles (like “Safety” at a nuclear plant). You should never change a value just to make it sound fresher. You must change a value if it has become an accidental obstacle to your new “diagnosis.”

Transformation Example#

Transformation and disruption necessitates a specific value architecture. The organization must be characterized by those who generate ideas and recruit others to join the cause.

| Desired Attribute | Strategic Implication | Required Value |

|---|---|---|

| Invention | Constant generation of new ideas; dissatisfaction with the status quo. | Curiosity / Dissatisfaction: The organization must value the question “Why?” over the statement “Because we’ve always done it this way.” |

| Mission | Rallying troops, driving change, pushing through inertia. | Bias for Action / Momentum: The organization must value movement and speed. “Let’s try it” must trump “Let’s study it.” |

| Empowerment | Dislike for merely supporting others’ ideas without agency. | Ownership / Agency: Employees are expected to take the ball and run, not wait for instructions. |

| Tenacity | Perfect is the enemy of good. Dislike for finishing touches, dotting i’s and crossing t’s. | Effectiveness: the organization must value effectiveness to ensure the disruption lands. |

This profile creates a natural tension with the “Steady Eddie” archetype: the employee who excels at execution and stability but resists change. If the organization’s values are set bottom-up by a majority of “Steady Eddies,” the “Disruptor" leader will find themselves at war with their own company. The values must be set top-down to explicitly protect the disruptive process, ensuring that “Steady Eddies” understand their role is to operationalize the disruption, not prevent it.

The Taxonomy of Values#

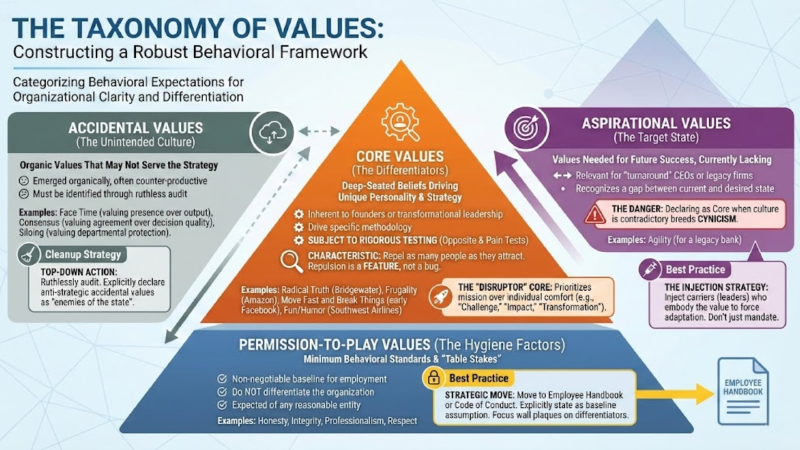

To construct a robust value system, one must distinguish between different categories of behavioral expectations. Following the frameworks popularized by thought leaders in team development like Patrick Lencioni, we can categorize values into four distinct tiers. This taxonomy allows leaders to declutter their “wall plaques” and focus on the drivers of behavior.

Permission-to-Play Values (The Hygiene Factors)#

These are the minimum behavioral standards required to be employed. They are non-negotiable, but they do not differentiate the organization. They are the “table stakes” of doing business. Examples: Honesty, Integrity, Professionalism, Respect.

The Strategic Trap: Many companies elevate these to “Core Values.” However, as noted in the section above on values as decision heuristics, a value is “useless” as a differentiator if no reasonable organization would claim the opposite. No company lists “Corruption” or “Dishonesty” as a value. Therefore, claiming “Integrity” is merely stating that the company obeys the law. It does not help a potential hire understand if they fit the specific culture of the firm.

Best Practice: Move these concepts to the Employee Handbook or the Code of Conduct. Explicitly state, “We assume you have integrity. If you don’t, you will be fired. Now, let’s talk about what makes us different.”

Core Values (The Differentiators)#

These are the deep-seated beliefs that drive the specific personality and strategic methodology of the firm. They are inherent to the founders or the transformational leadership team. These are the values that should be subjected to the rigorous testing methods described later (The “Opposite Test” and the “Pain Test”). Examples: Radical Truth (Bridgewater), Frugality (Amazon), Move Fast and Break Things (early Facebook), Fun/Humor (Southwest Airlines).

Characteristic: These values repel as many people as they attract. A person who values “politeness” over “truth” will be miserable at Bridgewater. A person who values “luxury” will be miserable at Amazon. This repulsion is a feature, not a bug.

The “Disruptor" Core: For the transformational leader, core values often revolve around “Challenge,” “Impact,” and “Transformation”. The core value prioritizes the mission over the comfort of the individual.

Aspirational Values (The Target State)#

These are values the organization lacks but realizes it needs to succeed in the future. This category is particularly relevant for “turnaround” CEOs or leaders injected into legacy firms.

The Danger: If an organization claims an aspirational value (e.g., “Innovation”) as a core value while its culture is actually bureaucratic, it breeds cynicism. Leadership must be transparent about the gap between the current state and the desired state.

Contextual Relevance: In the context of innovation, a legacy bank might need to adopt “Agility” as an aspirational value.

The Injection Strategy: To bridge the gap, the leader cannot simply mandate the value; they must “inject” carriers of that value into the organization. This mirrors Private Equity, injecting capability and expertise to “build the rocket” rather than just fueling it. These injected leaders serve as living embodiments of the aspirational value, forcing the organism to adapt or reject them.

Accidental Values (The Unintended Culture)#

These are values that have emerged organically but may not serve the strategy. Examples: “Face Time” (valuing being in the office over output), “Consensus” (valuing agreement over decision quality), “Siloing” (valuing departmental protection over enterprise success).

The Cleanup: Top-down value setting requires a ruthless audit of accidental values. If “Consensus” is an accidental value but the strategy requires “Speed,” the leadership must explicitly declare “Consensus” to be an enemy of the state.

The Reversibility Principle (The Opposite Test)#

One of the most robust mechanisms for validating a core value is the concept of “Reversibility” or the “Opposite Test.” This test posits that for a value to be legitimate and strategically meaningful, its opposite must also be a valid, viable business value.

The Mechanics of the Test#

When a leadership team proposes a value, they must ask: “Could a successful company exist that values the exact opposite of this?” If the answer is “No,” the value is a platitude (Permission-to-Play). If the answer is “Yes,” the value is Core.

Case Study A: “Integrity”#

- Proposed Value: Integrity.

- Opposite: Dishonesty/Fraud.

- Viability of Opposite: Zero. No sustainable business can be built on fraud. Even criminal enterprises value internal loyalty (a form of integrity).

- Verdict: Integrity is a Permission-to-Play value. It should be removed from the strategic differentiator list.

Case Study B: “Frugality”#

- Proposed Value: Frugality (e.g., Amazon’s “Accomplish more with less”).

- Opposite: Luxury/Opulence/Spare-no-expense.

- Viability of Opposite: High. Brands like Ritz-Carlton, Rolex, or Goldman Sachs may value “white glove service” or “premium inputs” over frugality. A private banker taking a client to lunch at McDonald’s (Frugality) violates the value of the firm (Opulence/Status).

- Verdict: Frugality is a valid Core Value because it forces a choice. It signals to employees that they should book the economy flight, not the business class seat, whereas at the opposing firm, booking economy might be seen as “brand damaging.”

Case Study C: “Collaboration” vs. “Individual Competition”#

- Proposed Value: Radical Collaboration.

- Opposite: Individual Meritocracy/Internal Competition.

- Viability of Opposite: High. Investment banks, real estate brokerages, and car dealerships often pit employees against one another to drive performance (e.g., “up or out” cultures).

- Verdict: Collaboration is a valid Core Value because it dictates a specific way of working that differs from the valid alternative.

Application in Transformation#

In the context of transforming legacy institutions or building “investable innovation”, this test is critical. A bank might claim to value “Innovation,” but if it is not willing to devalue “Stability” (the opposite), it is lying.

- Innovation implies risk, failure, and the obsolescence of old products.

- Stability implies predictability, risk avoidance, and the protection of legacy assets.

A transformation or disruption leader cannot tolerate a system or organization that values stability. By applying the Reversibility Principle, the leader clarifies that the organization values Change over Comfort, explicitly acknowledging that Comfort is a valid choice for other companies, but not for this one.

The “Table Stakes” Trap#

Finding “table-stake values” like integrity to be kind of “useless” is a key insight for the leader. The strategic purpose of core values is differentiation.

- Market Signaling: Customers choose brands because they stand for something specific. A customer chooses Southwest Airlines because they value “Fun/Low Cost.” They do not choose Southwest because they value “Integrity”. They assume it.

- Talent Signaling: High-performing talent looks for environments that match their working style. A developer who loves rapid prototyping (Speed) will be repelled by a company that values “Zero Defects” (Perfection). The Reversibility Principle ensures the company clearly signals which camp it belongs to.

The “Pain Test”: Testing Commitment to Values#

The second critical filter for a Core Value is the willingness of the leadership to suffer economic or operational pain to uphold it. If a value is compromised the moment it becomes inconvenient or expensive, it is not a value; it is a preference.

The “We’ll Miss You” Protocol#

A quintessential example of the Pain Test is found in the operational history of Southwest Airlines, a case frequently cited in high-level strategy discussions. When a customer wrote to CEO Herb Kelleher complaining about the flight attendants’ “unprofessional” jokes and humor during safety briefings, Kelleher did not apologize. He did not offer a voucher. He responded with a three-word note: “We’ll miss you.”

Strategic Implication:

- The Cost: The airline willingly lost a paying customer (revenue) to protect its culture.

- The Signal: This signaled to the employees that their behavior (Humor) was supported by leadership even when it caused friction with the market.

- The Filter: It reinforced that the airline is not for everyone. It is for people who appreciate that specific culture.

The “Hiring and Firing” Test#

The ultimate proof of a value is found in personnel decisions. A value is real only if the organization is willing to:

- Fire a High Performer: Dismiss a top revenue generator who violates the value. If a “star coder” or a “rainmaker” sales director is retained despite being toxic (violating a value of “Respect” or “Teamwork”), the value is void.

- Reject a Qualified Candidate: Pass on a candidate with perfect technical skills because they fail the “culture fit” assessment based on the values.

Operationalizing Values in Recruitment and Development#

Once defined top-down, values must be integrated into the mechanical systems of the firm. They must move from “Concept” to “Code.”

Values serve as a signaling mechanism to the market. A company’s values signal its identity to potential hires.

- Corporate Application: A company’s values page is its “Trust Banner” for culture. It must signal credibility and intent.

- Attraction/Repulsion: The goal of publicizing values is to attract talent that shares those values. E.g. attract the right “Crazy” and repel the “Steady Eddies” (or vice versa, depending on the values).

- The “Steady Eddie” Dilemma: Businesses need “Steady Eddies” for operations, but a “Disruptor” leader may find managing them draining. The value system helps sort talent into the right roles. A “Disruption” value attracts those who want to build the rocket; a “Stability” value attracts those who want to fly it.

Conclusion#

No business can afford the friction of a misaligned culture. This is perhaps doubly so in the case of transformation and disruption. Values are the mechanism by which such leaders scale their intent. By moving from a democratic, bottom-up model to a strategic, top-down architecture, and by rigorously testing values for reversibility and cost, organizations can transform their culture from a generic list of platitudes into a sharp-edged weapon for competitive advantage.

The result is an organization where innovation is not just a poster on the wall, but an investable, repeatable system of behavior. The goal is to find the unique intersection of passion, strength, and market need. Values are the compass for that journey.